Thoughts on s-curves

Bastiaan Terhorst, 23/11 '19

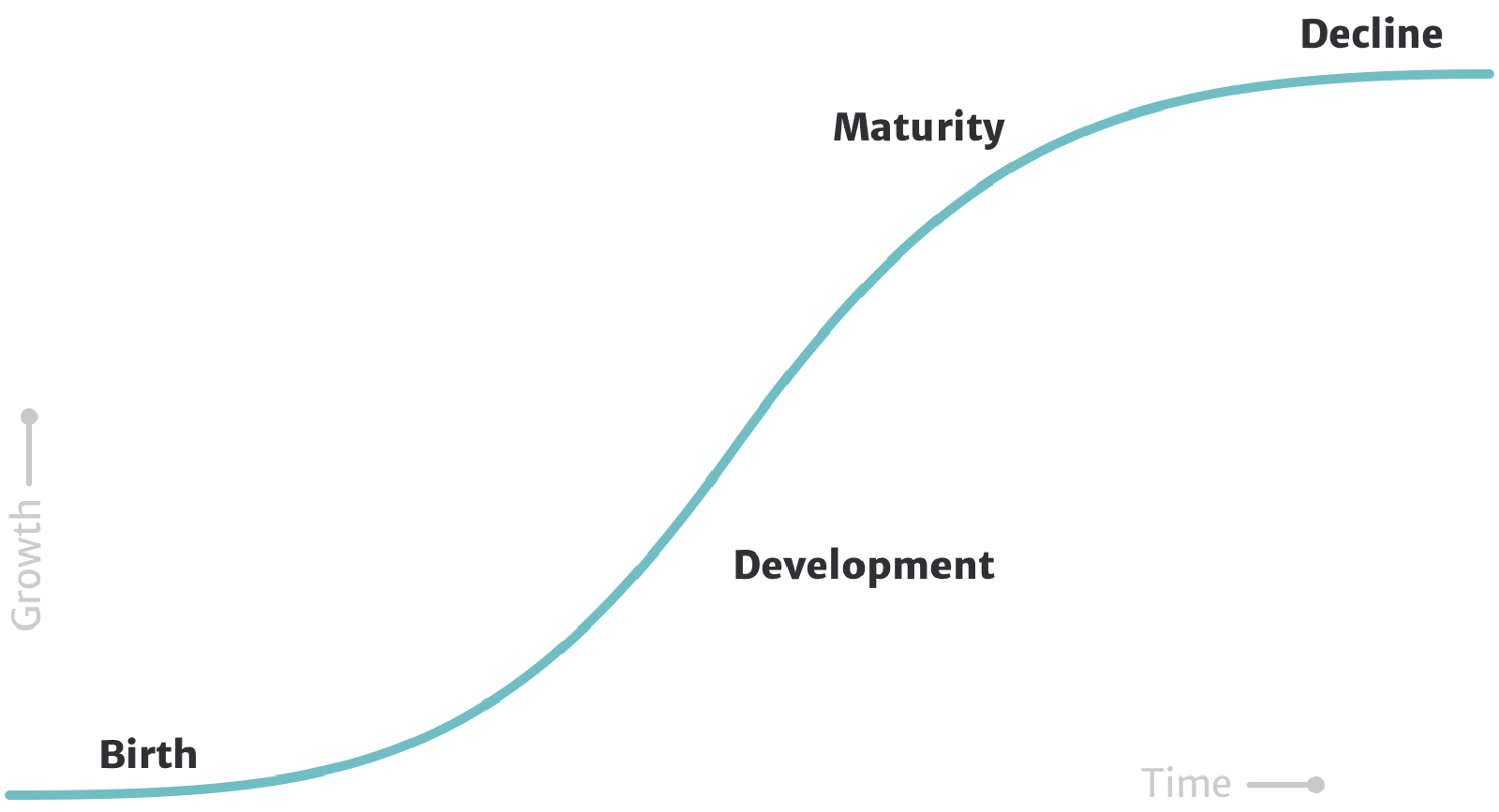

S-curves describe the growth cycle of systems. They describe the birth, development, maturity and eventual decline that we see around us; in nature, people, trends, companies, etc. They work at many levels of granularity: the growth of a flower can be visualised as an s-curve, and the growth of its petals as many smaller s-curves along that parent curve. This also works the other way around: we can zoom out and see that the curve of the flower is part of the s-curve of the spring season, with life erupting at its peak, and autumn ushering in the decline of that life as the curve comes to its end.

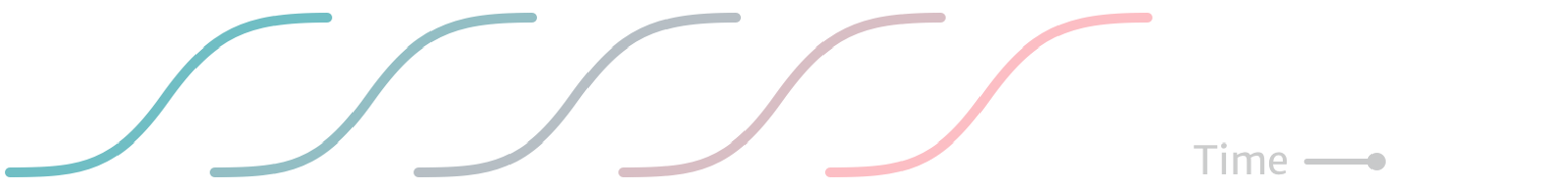

When the process of evolution produces a series of flowers that are each slightly different, this can be represented by a series of s-curves, each slightly different from the preceding one. The fact that evolutionary changes are minute from generation to generation make it possible for those changes to occur. An evolutionary process will not turn a flower into a healthy tree in a single generation. The gap is too large.

When we use s-curves to reason about the development of companies, products or other systems, the same applies. A company can go through developmental phases, reach maturity, and begin to explore a new developmental phase: a new s-curve. This new curve could be represented by a new product or market. For the employees and customers to make the jump to the new s-curve the company is trying to pursue, they need to be able to bridge the gap between the old and the new curves. Similar to how successful offspring of a flower will look very much like its parent, in order to bridge the gap in companies, there will need to be a certain commonality between the old and the new s-curve. When this commonality does not exist, in value proposition, culture, or purpose, the gap will be too large to bridge. People will fail to identify with the new initiative the company is trying to pursue. The new s-curve will fizzle out, and the old s-curve will decline (unless a new s-curve is started, and successfully this time).

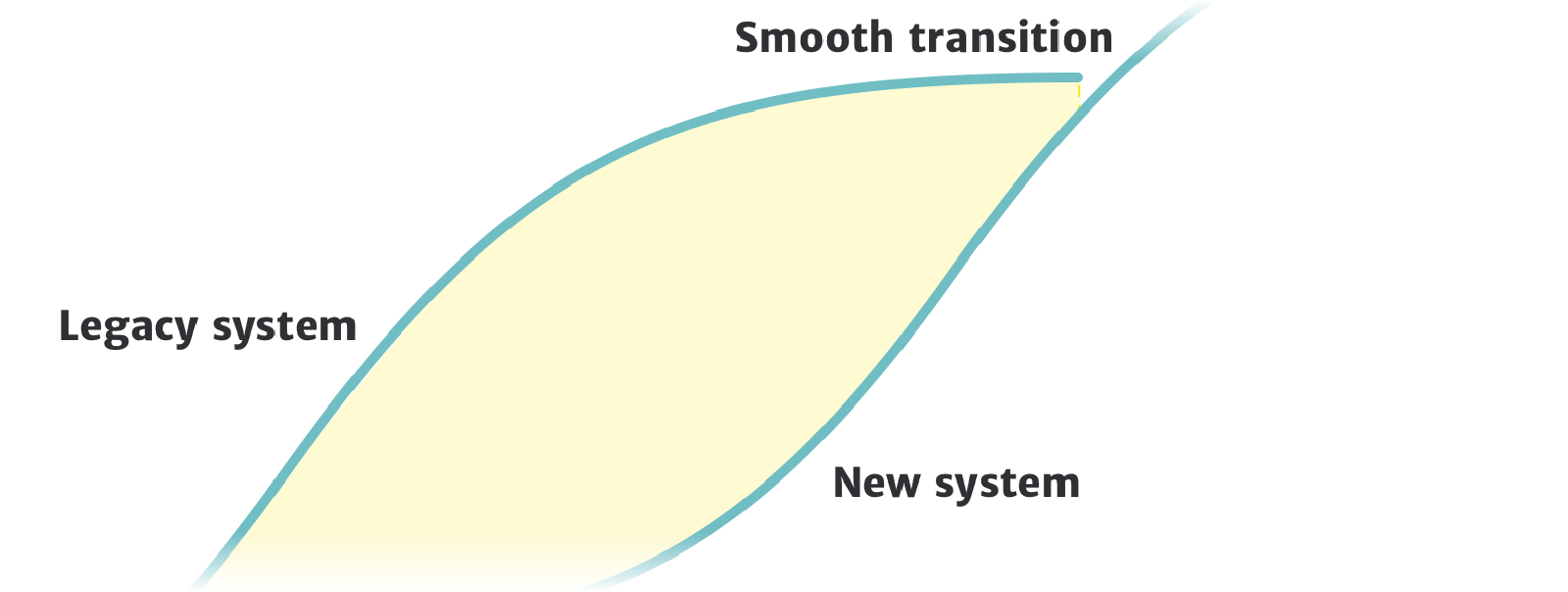

When we consider changing software systems, this can also inform our approach. Rather than replacing a system with something completely new and isolated from the systems’s predecessor, it is better to seek a certain level of commonality between the two systems and run them side by side, so that the maturity and decline of the old system lines up with the development and maturity of the new one. This process is also known as strangulation, which I have written about before. Another approach is to not replace a system at all, but to take a cue from nature and slowly evolve away from the present state in a succession iterations, which can be represented as s-curves. Each curve will take the new system farther away from the original state, and towards the desired end state.